The Life of a Respiratory Droplet

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has traditionally held that floors—in most situations—are “non-critical” surfaces when it comes to stopping the spread of infection. The organization has long believed that those surfaces we touch with our hands—typically referred to as high-touch surfaces—are those we must be most concerned about.

Consequently, floor hygiene is not that high on the CDC’s infection control and prevention list. This is true in all types of facilities, from health care (including pharmaceutical facilities) and education to commercial and office space.

However, even before the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers had begun asking the CDC to reconsider this stance. For instance, a 2017 study published in the American Journal of Infection Control concluded that floors harbor potentially dangerous germs that warrant reclassifying them as “critical” areas for disease transmission.

The researchers came to this conclusion based on studies in hospital settings where they found Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) on floors.

After health care workers touched objects that had been in contact with the floors, MRSA was found on the hands of 18% of the workers and VRE on 3%. But how did these and other pathogens get on the floor? There are many ways, but one of the most common is through the transmission of respiratory droplets from infected people.

Understanding human droplets and aerosols

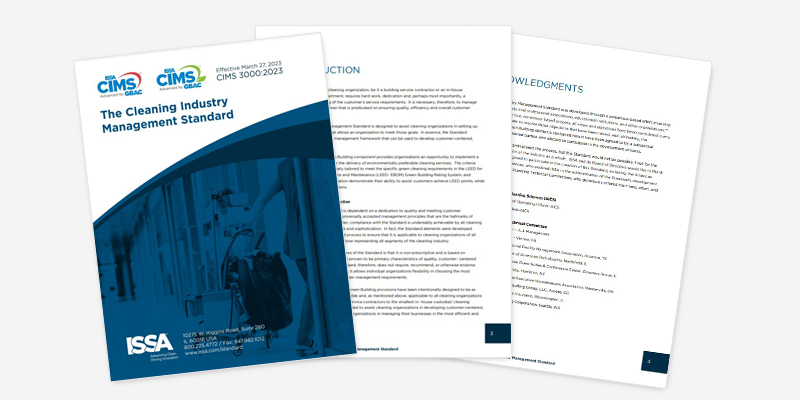

Before we begin our exploration, we should clarify that in May 2021, the CDC categorized three ways people could be infected by the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 and its variants that cause COVID-19 disease:

- Inhalation of air carrying very small droplets and aerosol particles that contain virus.

- Deposition of virus carried in exhaled droplets and particles onto exposed mucous membranes in the mouth, nose, or eye.

- Touching mucous membranes in the mouth, nose, or eye with hands soiled by exhaled respiratory fluids containing virus or from inanimate surfaces contaminated with virus.

With that said, typically, the life of a respiratory droplet starts with the following activities, cited in a classic study in the Edinburgh Medical Journal:

- Normal breathing from the nose—none, to a few droplets, that are then released into the breathable airspace.

- Talking loudly—a few dozen to a few hundred droplets.

- A single cough—up to a few thousand.

- A single sneeze—a few hundred thousand to a few million.

Along with knowing what human activities release the most droplets or aerosols, we need to understand trajectories. For example, if an infected person exhales, talks loudly, coughs, or sneezes, the respiratory droplets turn into aerosols and can travel as far as six feet from their source. During this time, they can be inhaled by others, spreading infection.

However, these droplets are generally not in the air for a long time. Instead, they soon land on nearby surfaces, including floors. But this is not necessarily their final resting ground.

Due to room airflow, pathogens may be stirred up and moved from one floor area to another area or surface. Further, pathogens can collect on mops and in the mop water during the floor cleaning process, spreading them from one floor area to another.

They can also be disturbed when someone walks over the floor. The droplets, formerly on the floor, can become airborne, which means that walkers inadvertently carry them a considerable distance, potentially spreading infection.

Eventually, however, they resettle on floors where they can pose a risk to anyone who comes in contact with them, directly or indirectly. This is how the health care workers mentioned earlier came in contact with MRSA and VRE—by touching objects that had been in contact with the floor.

Droplet death

When it comes to the life of a respiratory droplet, there is one final thing we need to discuss—death. Infectious respiratory droplets eventually die, but it is not always easy to measure how long they can survive.

For instance, the life span of a pathogen is typically measured in a laboratory setting where the indoor environment is controlled and hospitable to growth.

A pathogen that may live only a few minutes on a cold, dry office floor may live a few hours, even days, in a warm, moist lab setting.

Furthermore, even though a disease-causing pathogen is found on the floor or any other surface, it does not mean there is enough of the pathogen to make anyone sick.

“If a virus lands on something like a chair or table, it starts dying pretty quick,” explains infectious disease specialist and physician Frank Esper. “We may be able to find some viable virus after a few days, but it’s thousands of times less than what was originally deposited. As soon as the virus hits something that’s not alive, and certainly not a human, it’s not going to do very well.”

Our responsibility

Now that we have a better understanding of respiratory droplets, we need to emphasize that cleaning professionals can help minimize contact with disease-causing droplets and keep building users healthy. It is our duty and our industry’s calling. It starts with having an effective infection prevention and control program in place.

“Infection prevention in a facility must be wholistic,” said Patricia Olinger, executive director of the Global Biorisk Advisory Council® (GBAC®), a division of ISSA. “It is important that we complete a site and program risk assessment identifying the points of concern—items such as where are the touch points that you should focus on. We need to ensure that we are cleaning for health, what we are doing is making a difference, and measuring it. We must be putting in place a scalable response to become resilient.”

- Critical components of an effective infection prevention program include:

- Recognize that all usable areas of a facility may be “critical” when it comes to preventing the spread of infection. We can no longer wait for the CDC to recognize this fact about floors.

- Identify and record—in writing—all high-touch areas that need to be cleaned and disinfected, and how frequently. Formalizing this in writing helps to ensure these areas are cleaned and disinfected.

- Bring in a third party to walk through the facility to look for high-touch areas. A fresh set of eyes can find areas that are often overlooked.

- Know how and who uses a facility. Do children or older adults use the facility? If so, more intensive cleaning and infection control measures are necessary because these building users have weaker immune systems. Conversely, an office building with few children or older patrons may not require intensive cleaning.

- Select cleaning solutions, systems, and methods that have been proven to remove pathogens from surfaces.

- Floor mopping is the fastest and most efficient way to clean floors. However, mopping can spread contaminants. To prevent this, change mops and cleaning solution frequently, as often as after every floor area/room is cleaned. Consider using dual-bucket floor cleaning systems—one bucket houses cleaning solution and the other holds soiled water—to help prevent the spread of contaminants.

- Finally, test and test again. According to Steve Ashkin, president of The Ashkin Group and advocate for green cleaning and sustainability, the new Safety First credit from the U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED Rating System recommends the use of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) meters to measure cleaning performance, helping to ensure that surfaces are free of contamination. “The credit instructs cleaning professionals to prioritize high-touch spaces and surfaces. This can help cut down on the costs of using ATP meters [but still] ensure proper cleaning is performed when and where needed. Objective measurement is key to an effective infection control program.”

Understanding the life of respiratory droplets and aerosols can help us in the fight against infectious diseases.